George Nona

Details

Biography

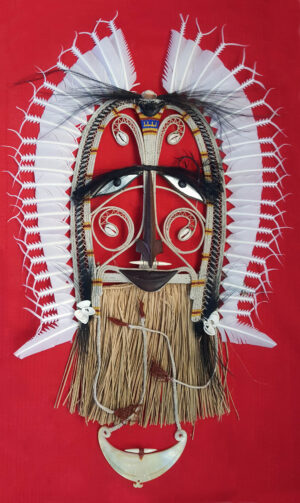

At the head of a grand tradition Nicolas Rothwell From: The Australian February 05, 2010 What are these? When Torres Strait Islander artist George Nona makes his dazzling headdresses, he is dealing with much more than mere beauty: he is plunged in the past, he is recapturing half-vanished memory, he is moving through the ancestral traditions of his island world.

His creations – known as Dhoeri in his western Torres Strait language – are pieced together from an elaborate set of natural materials: gleaming pearl shell, cassowary and eagle wing feathers, bone, cane, bamboo, beeswax, pigment. So delicate is the final structure that the headdresses shimmer and tremble even in the still, controlled conditions of a contemporary art space: they seem full of the pulse and movement of the ceremonial dances for which they were first made. Today, though, the Dhoeri are entering a new realm: they are being appreciated, and collected, as poised and subtle works, worthy of prolonged contemplation. A set of seven are on display this month at Sydney’s Hogarth Galleries, in an exhibition titled Muiyiw Minaral (Spiritual Markings).

Nona, brother of the celebrated Torres Strait printmaker Dennis Nona, is only one in a diverse group of young islanders engaged in a rediscovery of traditional crafts. But his journey towards artmaking was far from a natural, uncomplicated evolution. The little island societies of the Torres Strait, remote, tranquil, elusive, hold cultural complications worthy of a collection of Hellenic city-states. Nona was born in 1971 and brought up on Badu Island, famous for its warrior traditions, footballers and pearl-shell divers. His grandfather was a pearling-boat master there, well-known all through the waters of the strait. His father was a hardworking man with little time for the complexities of the old culture: the London Missionary Society, which shaped the life on the islands until mid-century, kept a firm check on the expression of old beliefs. It was a simple childhood: kerosene lamps and water from the well. Electricity didn’t come in until Nona had reached year 9.

“When we were children,” he remembers, “and we were growing up, that’s the time that we were told a lot of stories about how the life was before. The old people would tell us, quietly. Uncles, grandfathers – the island’s a small place, you sit down at night together, you listen to stories.”

Something caught, deep in Nona: what he heard and learned stayed with him. At school, in Cairns, there was a natural pathway open for him into art, and off to Canberra for art school training: it was a path taken by several of the talented young islander men he knew. But he chose work, cray-fishing, then bricklaying and building, first on Palm Island, then in Brisbane. All that time, though, he was on a secret trajectory of his own, going to museums, steeping himself in old books at the South Bank library reading room.

Like many islanders of his generation, he discovered the work of ethnographer Alfred Haddon, whose expedition had recorded in great detail the material culture of the Torres Strait. Haddon spoke to him in a direct fashion, for those pages held the history of his great-great-grandmother, recorded when she was a little girl in 1888.

Alone at his place in Brisbane, Nona began experimenting, making objects. He knew what he wanted to make: the bright, white-feather headdresses that lay at the heart of island memory. He worked in painstaking detail; he remembered everything the old men had told him. “That’s where I made the first one: in Brisbane, at 99 Croker Street.”

His brother Dennis saw the mask and was struck by it. It seemed natural that Nona should make more for the Badu island dancers. He had suffered an industrial accident and gone back to the Torres Strait and found ranger work. Slowly, over many months, following the descriptions passed down to him, he made a set of 18 ceremonial headdresses. He presented them to the Goeyga Pudhai dance group in mid-2002. By chance, just afterwards an old photographic plate of Badu dancers, taken in 1927, surfaced in England. The image reached the strait. Even Nona was astounded.

“When you compared the old photos with my headdresses, there was no mistake. Not one. That’s how perfect our oral history is as it’s handed down.”

This was like a signal for Nona. He held close to the old men, he learned whatever he could gather. “A lot of the men still know,” he says. “They have amazing information. Each headdress is a version of the words they’ve given me. You have to fish around. An islander won’t come up and tell you things, you have to ask. If he opens up to you, well, then you know that you’re really the right person.”

There were about 30 different types of Dhoeri, as he soon learned. Each one was made from different plants, seed-pods, shells and feathers. They were used by the various tribes to call on ancestral spirits before battles, or in ceremonies and rituals, or as markers of rank. Their memory had been preserved by the island dancers – but often at public events substitute headdresses had been worn, made from artificial materials, or even copied from the regalia of the western Strait. Now the dance tradition was restored; the Dhoeri were once more as they had been.

“I knew what I was doing,” Nona says. “That was always inside me, the memory and the respect for it. There was dancing practice going on all the time at our uncle’s house when we were boys. Dance was the expression of the old. It’s tied in with language.”

Like the other artists leading the Torres Strait cultural revival, Nona is convinced that language death would spell the effective end of distinct island identity. That threat is imminent.

“Who we are isn’t just held in the headdresses and the masks, or in the stories – it’s in the language you tell them in. We could be the last generation to fully understand the lingo, unless we try to preserve it. After us, it could be broken.”

Two years ago, Nona completed a second set of majestic Dhoeri for the local dancers. It was also the year he began making inroads into the fine-art world. His work was in the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art’s Optimism survey show; last year he won the Torres Strait indigenous art award with a large, complex “spiritual headdress”.

That piece, like several of the works in his present Sydney exhibition, was overlaid with intricate twined loops and pendant feathers, as well as a hanging, incised pearl-shell half-moon: the Dhibadib, which can represent a warrior going through initiation. The splendour of such works, their coded content, their detail and the outside admiration they excite all combine to strengthen the sense of cultural renaissance alive today on Badu and across much of the strait.

“Certainly, the feeling is changing,” Nona says. “It’s now seen as important, our culture. My generation, many of us are feeling hurt inside for what happened to our traditions, for what the missionaries have done. They took our headdresses and banned them and spoke against them in church. They found that in the Bible. They condemned our culture as evil. I was told by a couple of Christian relations that I was awakening the ancestral spirits with my work, and that was a dangerous thing to do.”

Nona falls silent – but in a sense, at least in a metaphorical sense, this is precisely what he is doing: bringing alive the past, revering it, seeking its strength in the present world, building a fresh tradition. Several prominent artists of the strait – Alick Tipoti in the west, Ricardo Idagi in the east – speak of feeling themselves lifted up and supported by the force of island tradition. So, too, with Nona.

“I could spend weeks on a single piece, months,” he says. “It’s not the time, it’s the feeling. It’s the way you make it, the feeling you get. The elders look at the work, they grade it: if they like one, it’s not just because it looks nice. No! When an islander looks at a headdress, his blood goes cold, because the feeling of dance and war is still inside there, it makes him feel vitalised, superior. And I have come to an area now where at last I understand. I might say, spiritually I am travelling into that area, it comes with constant practice, just as the old men told me.”

The masks, then, have gradually become much more to him than artefacts, neutral, attractive in their symmetries. They have a resonance for him. And for onlookers from the wider world? Nona’s art consists in conveying such emotions to external audiences, and this is done precisely by following the prescribed path, by being faithful to tradition.

Hence the quest for design authenticity, for the true materials, brought together in the right, the only proper way.

“My love for this work is great. I love making headdresses, I want to keep on making headdresses and masks all my life. I think it’s important. It identifies us, they are our roots, our culture, history: us.”

Artwork

-

AM 15629/18

$64,000 (tax inc.) View artwork -

AM 12551/16

$36,000 (tax inc.) View artwork -

AM 12546/16

$7,500 (tax inc.) View artwork -

AM 11170/15

$7,200 (tax inc.) View artwork -

AM 11167/15

$7,200 (tax inc.) View artwork -

AM 11166/15

$7,200 (tax inc.) View artwork -

AM 11164/15

$7,200 (tax inc.) View artwork

-

29 Hunter St, Hobart 7000,

Tasmania, Australia - +61 3 6236 9200

- euan@artmob.com.au

Cash – locally only – up to $10,000 only. Layby facilities available. Card details can be advised securely using WhatsApp.

© Art Mob Pty Ltd, Aboriginal Fine Art Dealer, all rights reserved.